On a whim yesterday I installed a new operating system on a old netbook. Looking at it makes me realise what we can do for the next wave of computing devices, even for things that are notionally “real” computers.

I’ve been hearing about Jolicloud for a while. It’s been positioning itself as an operating system for devices that will be internet-connected most of the time: netbooks at the moment, moving to Android phones and tablets. It also claims to be ideal for recycling old machines, so I decided to install it on an Asus Eee 901 I had lying around.

The process of installation turns out to be ridiculously easy: download a CD image, download a USB-stick-creator utility, install the image on the stick and re-boot. Jolicloud runs off the stick while you try it out; you can keep it this way and leave the host machine untouched, or run the installer from inside Jolicloud to install it as the only OS or to dual-boot alongside whatever you’ve already got. This got my attention straight away: Jolicloud isn’t demanding, and doesn’t require you to do things in a particular way or order.

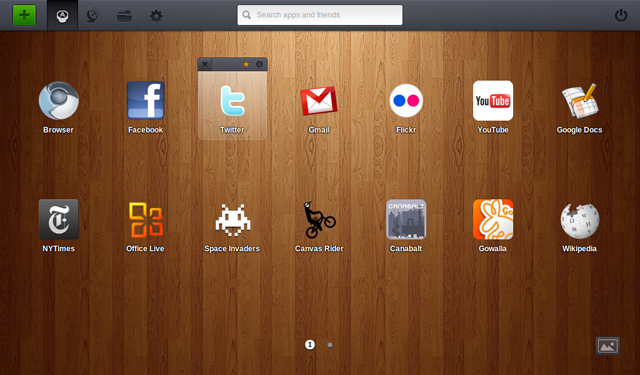

Once running (after a very fast boot sequence) Jolicloud presents a single-window start-up screen with a selection of apps to select. A lot of the usual suspects are there — a web browser (Google Chrome), Facebook, Twitter, Gmail, a weather application and so forth — and there’s an app repository from which one can download many more. Sound familiar? It even looks a little like an IPhone or Android smartphone user interface.

I dug under the hood a little. The first thing to notice is that the interface is clearly designed for touchscreens. Everything happens with a single click, the elements are well-spaced and there’s generally a “back” button whenever you go into a particular mode. It bears more than a passing resemblance to the IPhone and Android (although there are no gestures or multitouch, perhaps as a concession to the variety of hardware targets).

The second thing to realise is that Jolicloud is really just a skin onto Ubuntu Linux. Underneath there’s a full Linux installation running X Windows, and so it can run any Linux application you care to install, as long as you’re prepared to drop out of the Jolicloud look-and-feel into a more traditional set-up. You can download Wine, the Windows emulator, and run Windows binaries if you wish. (I used this to get a Kindle reader installed.)

If this was all there was to Jolicloud I wouldn’t be excited. What sets it apart is as suggested by the “cloud” part of the name. Jolicloud isn’t intended as an operating system for single devices. Instead it’s intended that everything a user does lives on the web (“in the cloud,” in the more recent parlance — not sure that adds anything…) and is simply accessed from one or more devices running Jolicloud. The start-up screen is actually a browser window (Chrome again) using HTML5 and JavaScript to provide a complete interface. The contents of the start-up screen are mainly hyperlinks to web services: the Facebook “app” just takes you to the Facebook web page, with a few small amendments done browser-side. A small number are links to local applications; most are little more than hyperlinks, or small wrappers around web pages.

The significance of this for users is the slickness it can offer. Installing software is essentially trivial, since most of the “apps” are actually just hyperlinks. That significantly lessens the opportunity for software clashes and installation problems, and the core set of services can be synchronised over the air. Of course you can install locally — I installed Firefox — but it’s more awkward and involves dropping-down a level into the Linux GUI. The tendency will be to migrate services onto web sites and access them through a browser. The Jolicloud app repository encourages this trend: why do things the hard way when you can use a web-based version of a similar service? For data, Jolicloud comes complete with DropBox to store files “in the cloud” as well.

Actually it’s even better than that. The start screen is synced to a Jolicloud account, which means that if you have several Jolicloud devices your data and apps will always be the same, without any action on your part: all your devices will stay synchronised because there’s not really all that much local data to synchronise. If you buy a new machine, everything will migrate automatically. In fact you can run your Jolicloud desktop from any machine running the latest Firefox, Internet Explorer or Chrome browser, because it’s all just HTML and JavaScript: web standards that can run inside any appropriate browser environment. (It greys-out any locally-installed apps.)

I can see this sort of approach being a hit with many people — the same people to whom the IPad appeals, I would guess, who mainly consume media and interact with web sites, don’t ever really need local applications, and get frustrated when they can’t share data that’s on their local disc somewhere. Having a pretty standard OS distro underneath is an added benefit in terms of stability and flexibility. The simplicity is really appealing, and would be a major simplification for elderly people for example, for whom the management of a standard Windows-based PC is a bit of a challenge. (The management of a standard Windows-based PC is completely beyond me, actually, as a Mac and Unix person, but that’s another story.)

But the other thing that Jolicloud demonstrates is both the strength and weaknesses of the IPhone model. The strengths are clear the moment you see the interface: simple, clear, finger-sized and appropriate for touch interaction. The app store model (albeit without payment for Jolicloud) is a major simplification over traditional approaches to maanaging software, and it’s now clear that it works on a “real” computer just as much as on a smartphone. Jolicloud can install Skype, for example, which is a “normal” application although typically viewed by users as some sort of web service. The abstraction of “everything in the cloud” works extremely well. (A more Jolicloud-like skin would make Skype even more attractive, but of course it’s not open-source so that’s difficult.)

Jolicloud also demonstrates that one can have such a model without closing-down the software environment. You don’t have to vet all the applications, or store them centrally, or enforce particular usage and payment models: all those things are commercial choices, not technical ones, and close-down the experience of owning the device they manage. One can perhaps make a case for this for smartphones, but not so much for netbooks, laptops and other computers.

I’m not ready to give up my Macbook Air as my main mobile device, but then again I do more on the move than most people. As just a portable internet connection with a bigger screen than a smartphone it’ll be hard to beat. There are other contenders in the space, of course, but they’re either not really available yet (Google Chrome OS) or limited to particular platforms (WebOS). I’d certainly recommend a look at Jolicloud for anyone in the market for such a system, and that includes a lot of people who might never otherwise consider getting off Windows on a laptop: I’m already working on my mother-in-law.

Once running (after a very fast boot sequence) Jolicloud presents a single-window start-up screen with a selection of apps to select. A lot of the usual suspects are there — a web browser (Google Chrome), Facebook, Twitter, Gmail, a weather application and so forth — and there’s an app repository from which one can download many more. Sound familiar? It even looks a little like an IPhone or Android smartphone user interface.

I dug under the hood a little. The first thing to notice is that the interface is clearly designed for touchscreens. Everything happens with a single click, the elements are well-spaced and there’s generally a “back” button whenever you go into a particular mode. It bears more than a passing resemblance to the IPhone and Android (although there are no gestures or multitouch, perhaps as a concession to the variety of hardware targets).

The second thing to realise is that Jolicloud is really just a skin onto Ubuntu Linux. Underneath there’s a full Linux installation running X Windows, and so it can run any Linux application you care to install, as long as you’re prepared to drop out of the Jolicloud look-and-feel into a more traditional set-up. You can download Wine, the Windows emulator, and run Windows binaries if you wish. (I used this to get a Kindle reader installed.)

If this was all there was to Jolicloud I wouldn’t be excited. What sets it apart is as suggested by the “cloud” part of the name. Jolicloud isn’t intended as an operating system for single devices. Instead it’s intended that everything a user does lives on the web (“in the cloud,” in the more recent parlance — not sure that adds anything…) and is simply accessed from one or more devices running Jolicloud. The start-up screen is actually a browser window (Chrome again) using HTML5 and JavaScript to provide a complete interface. The contents of the start-up screen are mainly hyperlinks to web services: the Facebook “app” just takes you to the Facebook web page, with a few small amendments done browser-side. A small number are links to local applications; most are little more than hyperlinks, or small wrappers around web pages.

The significance of this for users is the slickness it can offer. Installing software is essentially trivial, since most of the “apps” are actually just hyperlinks. That significantly lessens the opportunity for software clashes and installation problems, and the core set of services can be synchronised over the air. Of course you can install locally — I installed Firefox — but it’s more awkward and involves dropping-down a level into the Linux GUI. The tendency will be to migrate services onto web sites and access them through a browser. The Jolicloud app repository encourages this trend: why do things the hard way when you can use a web-based version of a similar service? For data, Jolicloud comes complete with DropBox to store files “in the cloud” as well.

Actually it’s even better than that. The start screen is synced to a Jolicloud account, which means that if you have several Jolicloud devices your data and apps will always be the same, without any action on your part: all your devices will stay synchronised because there’s not really all that much local data to synchronise. If you buy a new machine, everything will migrate automatically. In fact you can run your Jolicloud desktop from any machine running the latest Firefox, Internet Explorer or Chrome browser, because it’s all just HTML and JavaScript: web standards that can run inside any appropriate browser environment. (It greys-out any locally-installed apps.)

I can see this sort of approach being a hit with many people — the same people to whom the IPad appeals, I would guess, who mainly consume media and interact with web sites, don’t ever really need local applications, and get frustrated when they can’t share data that’s on their local disc somewhere. Having a pretty standard OS distro underneath is an added benefit in terms of stability and flexibility. The simplicity is really appealing, and would be a major simplification for elderly people for example, for whom the management of a standard Windows-based PC is a bit of a challenge. (The management of a standard Windows-based PC is completely beyond me, actually, as a Mac and Unix person, but that’s another story.)

But the other thing that Jolicloud demonstrates is both the strength and weaknesses of the IPhone model. The strengths are clear the moment you see the interface: simple, clear, finger-sized and appropriate for touch interaction. The app store model (albeit without payment for Jolicloud) is a major simplification over traditional approaches to maanaging software, and it’s now clear that it works on a “real” computer just as much as on a smartphone. Jolicloud can install Skype, for example, which is a “normal” application although typically viewed by users as some sort of web service. The abstraction of “everything in the cloud” works extremely well. (A more Jolicloud-like skin would make Skype even more attractive, but of course it’s not open-source so that’s difficult.)

Jolicloud also demonstrates that one can have such a model without closing-down the software environment. You don’t have to vet all the applications, or store them centrally, or enforce particular usage and payment models: all those things are commercial choices, not technical ones, and close-down the experience of owning the device they manage. One can perhaps make a case for this for smartphones, but not so much for netbooks, laptops and other computers.

I’m not ready to give up my Macbook Air as my main mobile device, but then again I do more on the move than most people. As just a portable internet connection with a bigger screen than a smartphone it’ll be hard to beat. There are other contenders in the space, of course, but they’re either not really available yet (Google Chrome OS) or limited to particular platforms (WebOS). I’d certainly recommend a look at Jolicloud for anyone in the market for such a system, and that includes a lot of people who might never otherwise consider getting off Windows on a laptop: I’m already working on my mother-in-law.