I recently tried out a new development environment for my Python

development, and noticed an unexpected convergence in the designs of

the two tools.

I’ve been a long-time Emacs user. I periodically

get a desire to try something new, something less old-school, just to

see whether there are advantages. There always are advantages, of

course — but often significant disadvantages as well, which often

keep me coming back to my comfort zone.

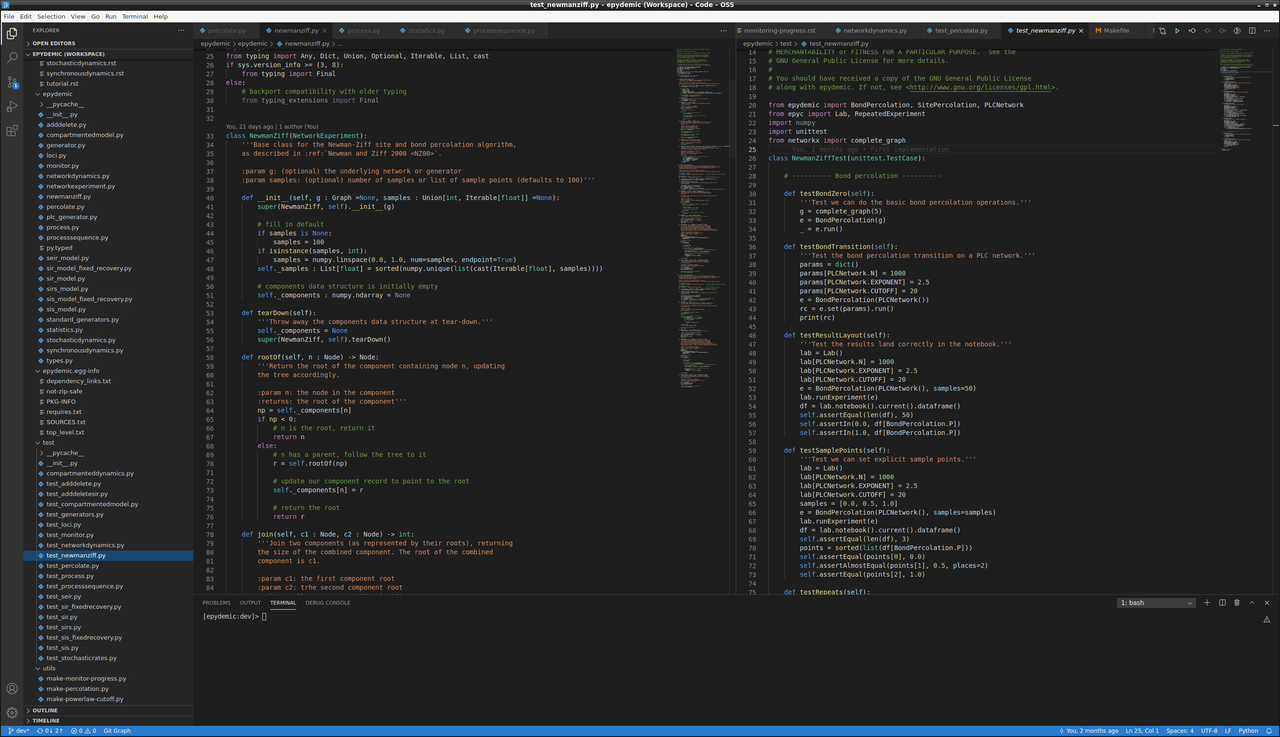

My most recent excursion was to try Microsoft’s VS

Code.

This is handily cross-platform, being built in Javascript on top of

Electron. It’s got a lot of nice

features: a tree view of the project in the left-hand pane, syntax

colouring, code style linting, integrated debugging and unit test

running, integrated connection to git, and so on. Looking a little

closer there are all sorts of status markers around the code and in

the ribbons at the bottom of panes and the window overall to show

status that might be important.

But it’s so slow. That’s a feature of VS Code, not of Electron (as I

first suspected), because other Electron-based editors like

Atom aren’t as slow. And my development box isn’t

the latest, but it also isn’t that old.

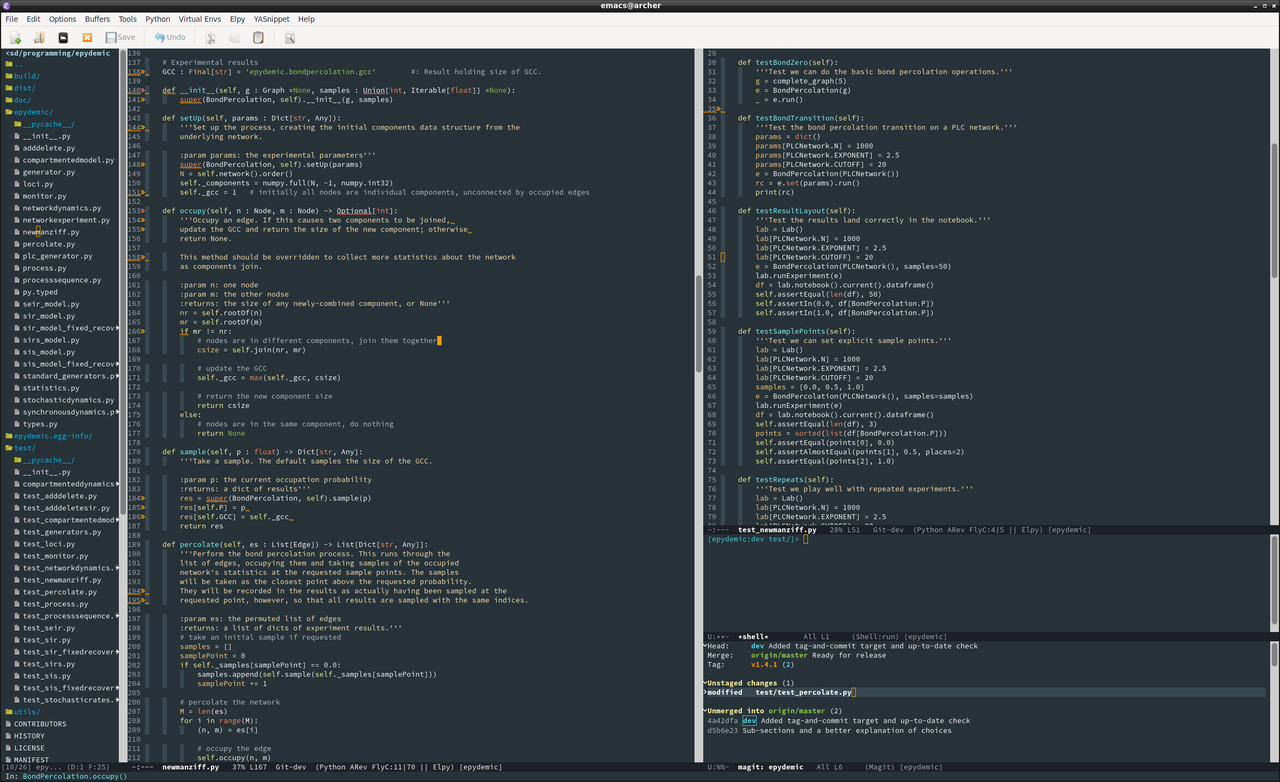

So I reverted to Emacs, but upgraded it a little to more modern

standards. Specifically, I installed the

elpy Python IDE,

with assorted other packages suggested by various sites. The result is this:

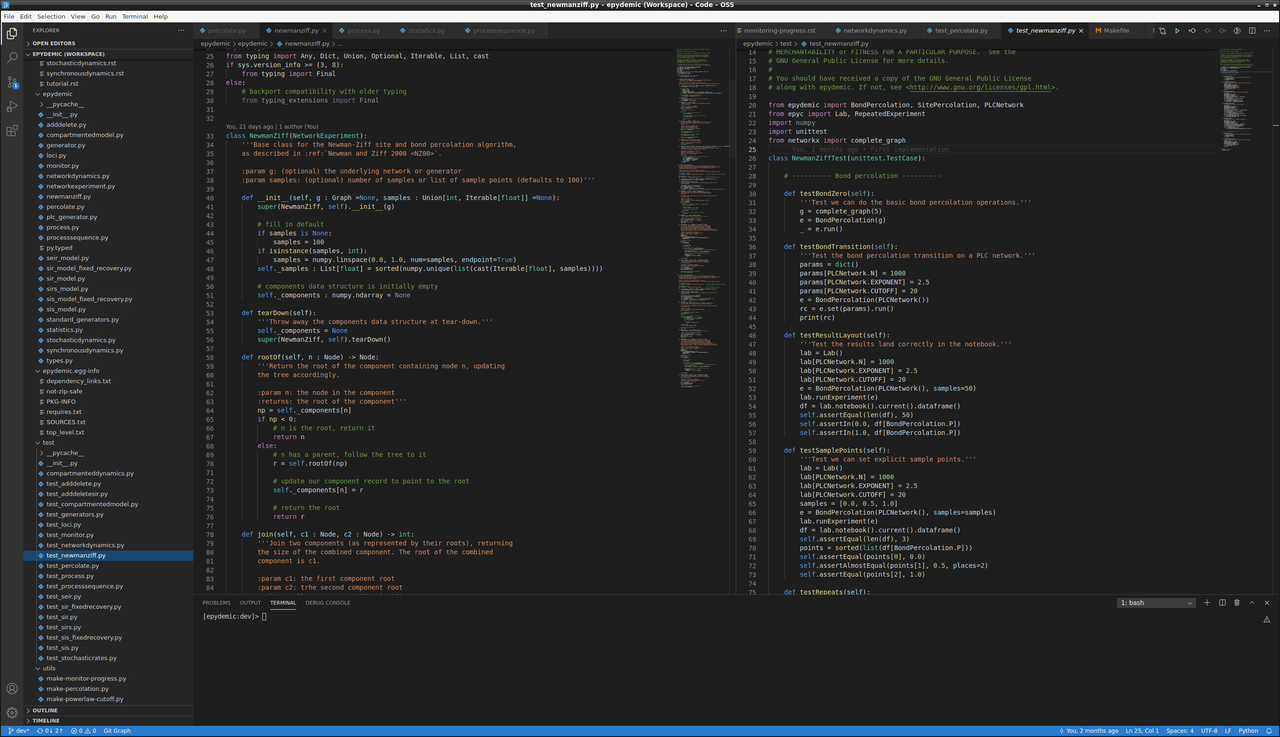

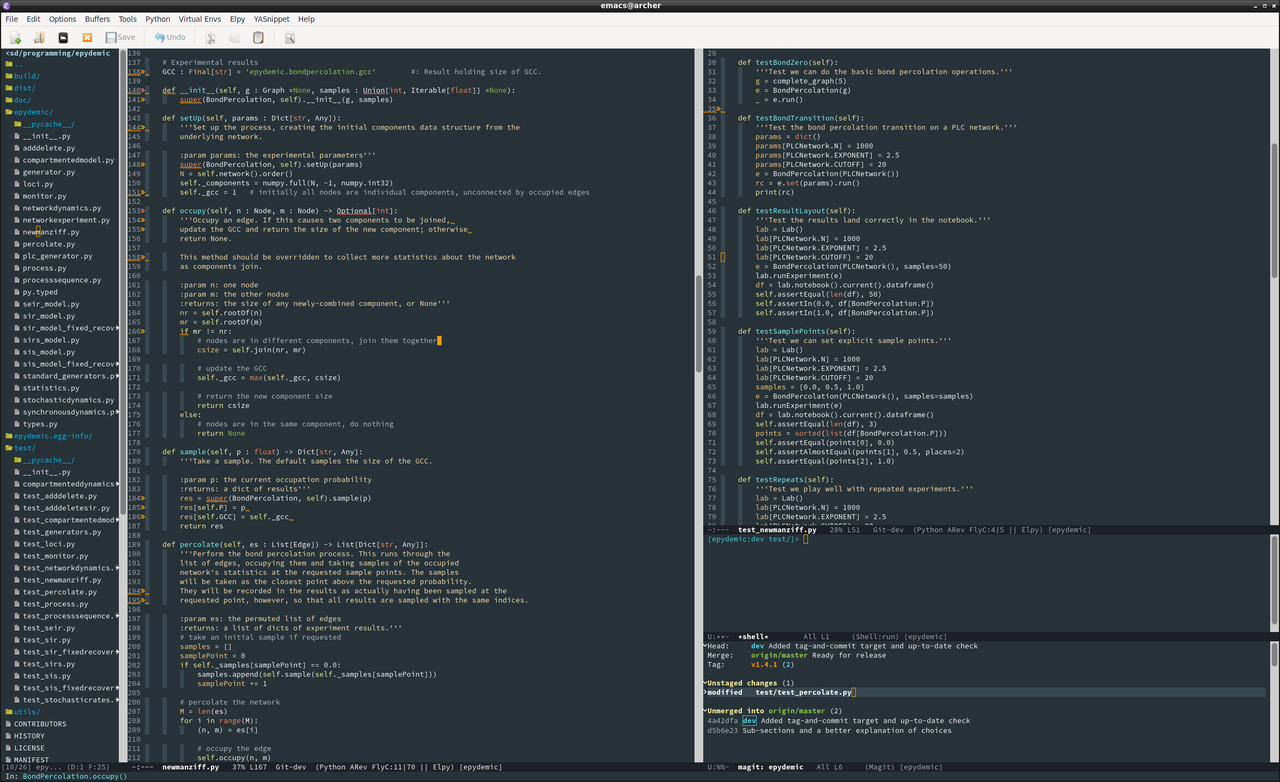

Now for anyone who’s used Emacs for a while, it’s definitely still

Emacs — not least with the convoluted keystrokes and infinite

customisation you either love or hate. But it’s striking how similar

the two IDEs now are, and striking how VS Code has inherited some

ideas from Emacs: resizeable panes, modelines in the ribbon, markers

in pane gutters, and so forth — things that Emacs-based applications

have had for years, which have now migrated into “the mainstream”.

Both the feature sets and the visuals of the two systems are very

similar indeed. Both are entirely cross-platform and extensible. For

VS Code you write extensions in Javascript; for Emacs you write them

in Lisp; and that’s about it. And Emacs is a lot faster on my

set-up. There are some limitations — I’ve yet to get the hang of using pdb as a debugger, for example, especially for modules

and from within tests — but the functionality is really quite comparable.

I think it’s safe to say there’s been cross-fertilisation between VS

Code (and other IDEs) and Emacs over the years. A lot of the

developers of the former quite possibly used the latter. But I

strongly suspect that most of the traffic has gone from Emacs to

the other systems: the similarities are just too great to be

accidental. It’s interesting to think that a system that emerged at

the dawn of the free-software movement has had — and is still having

— such an influence on modern development tools. And I’m happily back

in my comfort zone.