Are the international rankings indirectly fuelling the rise of MOOCs? And is there a positive feedback cycle at work?

The emergence of Massively Open On-line Courseware or MOOCs is being hailed as a disruptive moment in education, similar to the revolution that overtook the music industry. By unbundling modules from degree programmes and the universities who deliver them, the promise is to allow more personalised, varied, accessible, and (most importantly) cheaper education.

It’s easy to see how MOOCs benefit some students in some disciplines. Students living in remote places, from the developing world to the rural US (or rural Ireland, for that matter) can access courses from leading universities they would otherwise not be able to, or want to, attend physically. Students with disabilities, or those with significant work, family, or care commitments can more easily stitch education into their lives, freed from the constraints of structured and time-bounded degree programme. Modules available either free or at massively reduced cost will certainly broaden access and reduce the real or perceived elitism of the top institutions.

I think there are some serious caveats with the techno-utopian vision that’s being propagated, not least the suitability of MOOCs for many subjects and the way that much of the innovation is more about control than about openness — and these are topics I intend to return to. But for this post I want to focus on a narrower hypothesis: is there a positive feedback cycle in the economics of students and rankings driving at least some of the push towards MOOCs from some institutions?

What got me thinking about this is the release of the latest QS World Ranking of Universities. These are influential sources that (I can say from personal experience) influence students’ (and their parents’) choices about which university to attend. This is simply a fact: one can argue that position in a research-based league table will have only a moderate influence on an undergraduate’s university experience and later employability, but that’s doesn’t stop people considering the them important. Indeed, it is such an important factor that many universities publicly make being in the top 200, top 100, or even top 5 an institutional strategic goal that influences all their decisions. (For full disclosure, St Andrews comes comfortably in the top 100 universities in the world in this ranking, and doesn’t use ranking position as an element of its strategy. It’s nice for us to be highly ranked, but this is a consequence of our activities not a determiner of them.)

Rising up to the top of the tables is expensive, and I suspect that it gets exponentially more expensive to climb higher the higher up one is. The top-ranked institutions are amongst the richest in the world: Harvard, Stanford, MIT, and the like all have enormous economic power alongside their obvious and uncontested academic excellence. They are also major players in the MOOC space.

At first blush, this seems counter-intuitive. MOOCs are about cost reduction and breaking the power of traditional providers: why would the top universities be involved in this, when it seems at least possible that such a move will cannibalise their bricks-and-mortar students? It’s likely they don’t see this as a real threat, since they’re over-subscribed by several orders of magnitude more students than they can possibly accommodate. It’s also possible that they see MOOCs as a branding exercise rather than one of education, raising their profile at essentially no significant cost.

However, a more economic driver also occurs to me, at least when one moves down out of the elite stratosphere. Many institutions want to move up the league tables, which often involves going shopping for star academics: people whose research excellence enhances the reputation of their employers. As an institution gets more highly ranked, the quality of academic they need to have any impact on their position also increases, and as star academics are generally more expensive, improving ranking involves increased expenditure at each step. Increasing staff cost is therefore a consequence of a strategic decision to climb the rankings.

These stars and their research infrastructure have to be paid for, and in many systems these costs more or less trickle-down to student fees. Education inflation is running well ahead of general price inflation in the US (see for example this article from 2012), and a large chunk of this comes from academic salaries. (Admittedly an even larger chunk comes from increased administration.) The problem is that this inflation sets up a countervailing pressure, as students look at the costs of their education in terms of accrued student debt and contrast it against expected lifetime earnings — and in some cases decide it’s not a sufficiently valuable proposition. Physical institutions can’t simply grow their numbers, since students attending a university have overhead costs: they have to be accommodated nearby at a price they can afford to pay, if nothing else. The pressure therefore builds up to reduce student costs while keeping the size of the student body roughly constant.

This is where MOOCs might come in. Star academics have celebrity that can be leveraged by getting them to develop MOOC courses that can be sold worldwide. Even a trickle of income (from up-front registration or charges for certification) provides a revenue stream that can be used to reduce the costs for traditional students. MOOC development is sometimes seen as cost-free (since the staff are in place already), and so the revenue feels like money for nothing. But as MOOCs become more popular, institutions require more MOOCs, and more star academics to make them, and hence more revenue to pay for these individuals and their research, and so more MOOCs: a feedback loop that might actually become self-sustaining, a bubble in MOOC provision driven by a desire for increased international rank with a stable bricks-and-mortar student body.

Any such bubble will be an issue for universities of less exalted status, since the provision of free courses from elite institutions looks set to change how students seek out knowledge, despite the fact that not everyone is an autodidact who can learn by themselves. It’s still not clear what impact MOOCs will have on education in its broadest sense, and there are certainly many positive aspects that we’re interested in exploring ourselves. A self-fulfilling bubble is however not something we should be indifferent to.

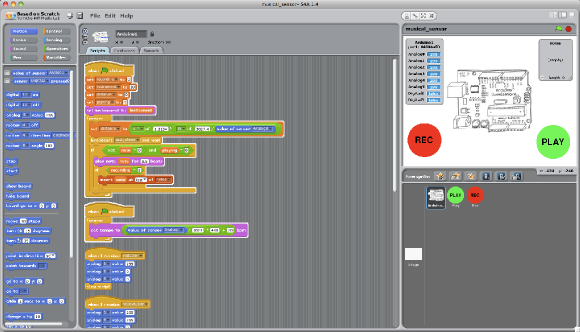

A Scratch program

It’s hard to describe exactly how this sort of visual programming works, and it’s definitely not suitable for all tasks: typically it’s better for exploratory and experimental, “play” approaches rather than more detailed and complex processes. But it’ll be great to see whether this is appropriate for many of the applications the Arduino finds a home in — and even more so to explore it for what we’re trying to do here at Citizen Sensing.

A Scratch program

It’s hard to describe exactly how this sort of visual programming works, and it’s definitely not suitable for all tasks: typically it’s better for exploratory and experimental, “play” approaches rather than more detailed and complex processes. But it’ll be great to see whether this is appropriate for many of the applications the Arduino finds a home in — and even more so to explore it for what we’re trying to do here at Citizen Sensing.